Among the weapons carried by the

Aborigines of the Monaro were tomahawks, fashioned of stone, which they

obtained near the Snowy River, at Buckley's Crossing. Basalt, or diorite

chips, and complete weapons were still found in the area in 1926 (Mitchell 1926:35).

On the upper reaches of the Snowy River, close to the Eucumbene River, another

area also provided similar raw material for Aboriginal implements. The

original inhabitants knew it as Giandarra and its name meant 'stone used for

making knives' (Department of Lands 1959). Giandarra, variously called

Gorandarra (Gregors 1982:4), Goandara (Clarke 1860), Giandara (Moye 1959:9) and

Guyandra (Dowd), later became known as Kiandra under European occupation.

Aboriginal

people had been visiting these areas of the highlands of south-eastern

Australia for over 20,000 years and, as with the rest of Australia, the region

was the territory of a particular group or "tribe" with its own

language and identity (Flood 1996:3). Aborigines who spoke the Ngarigo language

inhabited most of the Snowy Mountains, and the surrounding uplands, for a

distance of about 200km to the north and south, and east for about 120km from

Mount Kosciusczko, which was on the western boundary of Ngarigo territory. A

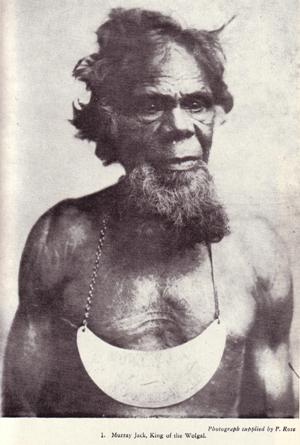

neighbouring linguistic group, the Wolgal (also called the Walgalu), was

probably a sub-group of the Ngarigo. The Wolgal were located at the headwaters

of the Murrumbidgee and Tumut rivers, at Kiandra, south to Tintaldra, and

northeast to near Queanbeyan (Tindale 1974:199).

Long

before the arrival of Europeans, these groups intensively exploited the food

resources of the upper montane valleys and alpine zone of the Snowy Mountains

during the summer months (Flood 1980:127). In early summer Aborigines from

surrounding and more distant regions joined them. Non-resident Ngarigo

speakers came from the Monaro district immediately to the north, Ngunawal

speakers from the southern tablelands, and Yuin speakers from the south-east

coast of Australia, while other groups arrived from territory to the south of

the Snowy Mountains (Flood 1980:73). At such time hundreds and possibly well

over a thousand Aborigines, belonging to at least three major language groups,

gathered to strengthen social and political links, and to feast upon a unique

food source in the southeastern highlands - the small brown Bogong moth (Agrotis

infusa).

Millions of these moths aestivate during summer on the mountains tops of the

Great Dividing Range in the Australian Capital Territory, the Snowy Mountains

and the Victorian Alps (Flood 1996:12). Aborigines had gathered in such

numbers to harvest the moths for thousands of years. However, due to major

demographic and social changes that had occurred in south-eastern Australia as

a result of European settlement, it is likely that the composition of tribal

groups and sub-groups seen by early white settlers at these ceremonial grounds

may not have been exactly the same as in pre-contact times (Kamminga 1992:106).

The

importance of this unique food source and therefore the importance of the

region to Aboriginal people should not be underestimated. Its significance to

social, political and economic alliances between different language groups in

south-eastern Australia can be seen in the large number of people in attendance.

The event was certainly a significant one if, of the possibly 25,000

Aborigines in NSW in the 1840s and 1850s (Jupp 1988:76), perhaps over 1,000 (or

over 4%) of them attended the annual congregation in the Snowy Mountains

region. The estimated lower population density of the Monaro and the Southern

Tablelands compared to other richer coastal or riverine areas of NSW (Flood

1996:36) also adds statistical weight to the importance of the gatherings. The

density of Ngarigo people was estimated to be 1 person per 36 square kilometres

in 1828 compared with 1 person per half a kilometre in Sydney in 1788 (Gregors

1982:26). Although these gatherings continued, and were well attended, into

the 1850s and early 1860s, declining numbers and shattered social and economic

conditions resulted in the last moth hunt being held in 1865 (Flood 1996:17).

Nevertheless,

initial contact between Aborigines of the Snowy Mountains region and Europeans

appears to have been peaceful. On the first official exploratory journey southwards,

towards Cooma in 1823, Currie and Ovens met a group of Aborigines who had never

seen Europeans and who fled at their approach. With the help of their

Aboriginal assistant, and biscuits, the two groups parted on friendly terms

(Mitchell 1926:18). Further to the southwest, when exploring the Tumut

district in 1824-25, Hume wrote in his diary of having met a party of

Aborigines in the Tarcutta area

We came on by surprise

a party of eight men who, on seeing our bullocks, fled and concealed themselves

in some reeds on a creek. One of these men was dressed in an old yellow jacket

and spoke a few words of English and had been to Lake George. They had among

them one iron axe and four steel tomahawks. The next day about 40 able bodied

men returned and asked us to go to their camp so that the women and picaninnies

could see us. . . . Many of the children took hold of my hands and patted me.

At the request of the men I named some of the children. . . . The men were the

finest specimen we have ever seen, some standing six feet tall and well

proportioned, and possessed what is unusual among natives, well formed legs. .

. . (Bridle 1979:5-6)

On

the whole, the Aborigines of the Snowy Mountains region appear to have

continued such amicable relationships with the first white settlers who arrived

in the area, possibly as early as 1828. However they could not escape the

ravages of the diseases that preceded and accompanied the Europeans, or the

upheaval of their traditional lifestyles.

As

with most of the rest of Australia, the Aboriginal population of the Snowy

Mountains region began to decline not long after the arrival of white settlers

in the area. The Aboriginal groups living on the tablelands northeast of the

Snowy Mountains were disintegrating by at least 1834 (Lhotsky 1835). William

Hamilton, a Presbyterian Minister appointed by the Presbytery of NSW to perform

pastoral duties in the county of Argyle and adjacent parts wrote to a friend in

March 1839 that

The

Aboriginal natives are not very numerous yet a few are found everywhere. I

believe they have very much decreased since the settlers with their convict

servants came among them and they are likely to decrease, not that they are now

frequently killed by the whites in these parts which have been for some years

settled but because they have few children or at least few that are seen

growing up. (Hamilton, 16th March 1839)

In

January 1842, John Lambie, the "Commissioner of Crown Lands for the

District of Maneroo to the Eastward of the Snowy Mountains in New South

Wales", wrote that

The aborigines of this

district, with the exception of the coast tribes, may be said to be almost in

their primitive state. . . . The natives belonging to the tribes to the

westward of the coast range are very little employed by stock owners, except a

few occasionally, in washing sheep; they preserve their original habits of

hunting, and are constantly moving from place to place (Mitchell 1926:35)

It

even appears that the Snowy Mountains themselves were unkind to the dwindling

Aboriginal population of the area. The Rev. W.B. Clarke who traversed the

southern alpine area during 1851 and 1852 testifies to the severity of the

climate and its effects on a party of Aborigines

. . . though not ready

to shrink from difficulties and not unwilling to encounter adventures, I did

not think it prudent to contend with the inclemency of the approaching winter

in an inhospitable position among the mountains; when I recollected that the

month was May [1852], and that in the month of March preceding, a party of

Aborigines, coming from the Murray River to Maneroo, were overtaken in a snow

storm, and that, whilst one man was severely frost-burnt and crippled, two

others were completely smothered in the drift, within a short distance of the

very spot upon which I and my party encamped on the 22nd and 23rd

December, 1851 (Clarke 1860:221).

Despite

a rapidly declining population and overwhelming European influence, those

remaining Aborigines in the Snowy Mountains region sought to retain their traditional

ways into the 1860s. W.P. Bluett wrote that his father bought Pinbean run in

1858. The farm included land from the Yarrangobilly River near the Caves to

the Tumut River. The homestead was about 20 miles (32km) from what was later

called the Kiandra Diggings. Due to the unavailability of white labour at the

end of the 1850s and into the 1860s, his father employed Aborigines to work as

station hands on the farm, but that they were found to be inefficient because

of their "compelling walk-about" (Moye 1959:2).

Possibly

the only direct observation of Aborigines at Kiandra was in 1877 by Mr Tyers, a

Government official. He wrote of "a small and pathetic group of the

remnants of a number of tribes that frequented the alpine goldfields, addicted

to opium" (Feary 1994:10). The last of the 'tribal' Aboriginal people of

the Tumut area died in the 1870s (Bridle 1979:6), Nellie Hamilton, the last

'tribal' Aborigine of the Canberra district died in 1897 (Flood 1996:37), and

Biggenhook, the last 'tribal' Aborigine of the Cooma area, died in 1916 aged

about 62 (Mitchell 1926:35).

Lindsay M. Smith

BA UNE, GradDipArts(Prehistory) MA ANU

January 2004

~ o0o ~

References

Bridle, J., 1979, Talbingo, Tumut & Adelong Times, Tumut, NSW.

Clarke, W.B., 1860, Researches in the Southern Gold Fields of New

South Wales, Reading and

Wellbank, Sydney.

Department of Lands, 1959, Letter to Mr. D. Howard concerning the centenary of

the Kiandra

gold rush, 10 February 1959.

Feary, S., 1994, Draft Management Plan for Kiandra, NSW National Parks and Wildlife

Service.

Flood, J., 1980, The Moth Hunters,

Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, Canberra.

Flood, J., 1996, Moth Hunters of the Australian Capital Territory:

Aboriginal traditional life in

the Canberra region, J. M. Flood, Canberra.

Gregors, G., 1982, Kiandra Precinct Plan, a management plan prepared for National Parks and

Wildlife Service, April 1982.

Hamilton, W., 1839, Letter to John Res Esq. Greenock, 16th

March 1839, Unpublished

Manuscript, National Library of Australia, MS 2117.

Jupp, J., 1988, Australian encyclopaedia.

Kamminga, J., 1992, 'Aboriginal Settlement and Prehistory of the Snowy

Mountains', in

B. Scougall (ed.) Cultural Heritage of the Australian Alps:

proceedings of the 1991

Symposium, Australian Alps Liaison

Committee.

Lhotsky, J., 1834, A Journey from Sydney to the Australian Alps,

Undertaken in the Months of

January, February and March 1834,

Geological Society, London.

Mitchell, F.F. (ed.), 1926, Back to Cooma Celebrations, The Direct

Publicity Company, Cooma.

Moye, D.G. (ed.), 1959, Historic Kiandra: a guide to the history of

the district, Cooma-Monaro

Historical Society, Cooma.

Tindale, N.B., 1974, Aboriginal Tribes of Australia: Their terrain,

environmental controls,

distribution, limits, and proper names,

Australian National University Press, Canberra.

~ o0o ~

Back to Top Copyright | 2025 | kiandrahistory.net